Mauthausen. I conti con il passato, nel presente

«In un paese, riluttante per decenni a riconoscere le proprie responsabilità per i crimini nazisti, la coscienza pubblica della responsabilità nel presente è simbolicamente alta, ma non nei fatti. Questo vale per l'Austria in quanto paese e in particolare per il suo punto focale per quanto riguarda la memoria e la didattica: l'ex campo di concentramento di Mauthausen».

Inizia così l'articolo in inglese, che pubblichiamo qui in anteprima, con il quale l'austriaco Wolfgang Schmutz – che fino all'anno scorso dirigeva de facto il dipartimento pedagogico (l'educational team) del Mauthausen Memorial – scaglia il suo atto d'accusa contro le politiche della memoria austriache degli ultimi anni. Il testo è scritto per essere diffuso a livello internazionale, e penso che sia importante che veda la luce inizialmente in Italia, dal momento che il memoriale, che ospita «oltre 3000 gruppi di visitatori all'anno», vede gli italiani in seconda posizione, in quanto «il più consistente gruppo di visitatori non germanofoni».

Questo dovrebbe rendere l'opinione pubblica italiana, e non solo gli addetti ai lavori, sensibile alla discussione che Schmutz vorrebbe suscitare, e in particolare al tema della distanza siderale tra le intenzioni dichiarate delle politiche della memoria (in Austria e in generale in Europa) e la realtà dei fatti.

Mauthausen, nel corso del secondo conflitto mondiale, fu uno dei lager nei quali affluì il maggior numero di deportati italiani, e soprattutto fu quello, anche in ragione della considerevole produzione di memorie dei suoi sopravvissuti, che rimase a lungo l'immagine della «parte per il tutto». Per lunghi decenni, prima dell'istituzione del Giorno della Memoria (20 luglio 2000), nella memoria pubblica italiana per dire “lager” non si diceva “Auschwitz”, ma “Mauthausen”.

«Il memoriale è amministrato e gestito in modo profondamente non professionale, con un budget completamente insufficiente», lamenta Schmutz. Ci racconta come due anni fa non venne rinnovato il contratto al direttore del suo dipartimento ma, nonostante la sospensione dei programmi educativi e della formazione delle guide, il gruppo di lavoro del quale lui faceva parte si rimboccò le maniche e continuò a proporre delle visite che sono complementari all'approccio che è implicito nel percorso di visita così come è strutturato “ufficialmente”. Forse addirittura in contrasto, dal momento che “fare memoria” significa innanzitutto scegliere quale è il frammento di storia che vogliamo raccontare. E le guide hanno ben chiaro su cosa è cruciale soffermarsi.

«Le visite guidate […] portano i visitatori attraverso le parti esterne alle mura [del lager] e di conseguenza interrogano il coinvolgimento della società austriaca nel fenomeno dell'esistenza del campo, sono – a parte le piccole sezioni dei nuovi percorsi espositivi – solamente le visite guidate che affrontano il tema dell''essere carnefici' e dei legami poliedrici tra la società nazista e i crimini commessi nel campo di concentramento di Mauthausen».

«Queste omissioni al Mauthausen Memorial – prosegue Schmutz, ponendo tra le righe la questione a livello europeo – devono essere discusse a un livello più alto e più ampio». Nonostante gli sforzi marginali, aggiunge, gli uomini e le donne che hanno l'incarico di dirigere le attività del memoriale si dipingono come dei grandi attori di cambiamento. Eppure, «da quando Mauthausen divenne un memoriale – continua Schmutz –, fu organizzato come un 'palco' per la politica interna e internazionale, inquadrato quasi esclusivamente da un punto di vista austriaco».

Le parole con cui Schmutz vuole aprire il dibattito sul ruolo che il Mauthausen Memorial svolge nella costruzione della memoria pubblica austriaca ed europea vanno prese, credo, estremamente sul serio. Senza partigianerie, ma con l'obiettivo di interrogarsi su quali possono essere le pratiche da mettere in campo a livello internazionale e quali i temi da sollevare per dare sostanza a quel “mai più” che in Italia si ripete ossessivamente negli ultimi quindici anni, dall'istituzione del Giorno della Memoria. Nonostante l'impatto dei crimini commessi, che fu “internazionale”, aggiunge Schmutz, il memoriale – gestito dal Ministero degli Interni austriaco – non è percepito come tale, ma come luogo per raccontare l'Austria (e la sua memoria) all'esterno. Con il rischio di – più che fare i conti con il passato – farsi degli sconti. E non è il solo “luogo di memoria” che esita nell'affrontare il tema delle responsabilità di molti propri connazionali del tempo che fu, rimanendo ancorato a delle narratives che sono in parziale opposizione con quanto gli stessi lavoratori e collaboratori del memoriale, spesso preparatissimi, sanno e – a quanto pare – vorrebbero dire.

«[....] la maggior parte dei professionisti del memoriale (negli archivi e nel dipartimento pedagogico) non hanno contratti stabili, e la loro possibilità di esprimersi è limitata da gerarchie formali e informali». Come loro anche gli storici coinvolti, sostiene Schmutz, i quali «evitano di prendere posizione pubblicamente e con chiarezza» sulle politiche della memoria con le quali viene gestito l'ex lager e intorno alle quali si sono costruiti i suoi nuovi percorsi espositivi.

Gli esempi che l'operatore culturale austriaco porta a sostegno della sua tesi sono nel testo integrale in inglese, ma ci mostrano la passione con cui negli ultimi anni Wolfgang Schmutz si è messo al servizio della coscienza pubblica europea; con lui i suoi colleghi e le sue colleghe che con il lavoro quotidiano hanno raccontato come il campo di Mauthausen non sorse in un deserto, ma in una regione, in un paese e in un continente in cui dilagavano anche (soprattutto?) l'indifferenza e la complicità. Il primo di questi cerchi concentrici lo ha raccontato lo storico Gordon J. Horwitz nel libro All'ombra della morte. La vita quotidiana attorno al campo di Mauthausen (Marsilio 1994, ed. or. 1990), gli altri sono ancora in gran parte da raccontare con onestà intellettuale e la consapevolezza di essere degli story-tellers. Consapevolezza che molte guide del Mauthausen Memorial, che ho più volte visto all'opera, hanno certamente. Il Terzo Reich, con l'intento di farsi Impero, travolse ogni confine nazionale. Perché noi, oggi, nel ricordare le esistenze di uomini e donne più o meno comuni che fecero i conti con le persecuzioni e lo sterminio, non siamo in grado di fare altrettanto? Come si costruisce una memoria pubblica europea che “serva” veramente alle nuove generazioni, se non partiamo dall'assunto – oltre le narratives “nazionali” – che furono ben pochi coloro che non vennero travolti dall'Europa dei fascismi che contaminò così tante coscienze, non molto tempo fa?

Credo che oggi, che ricorre il settantesimo anniversario della liberazione del complesso concentrazionario di Mauthausen, per noi cittadini del “post-Holocaust world” porsi domande di questo genere sia il modo più costruttivo di “fare memoria”. Per ripartire.

Carlo Greppi

Il "Kameradschaftsbund" di fronte a una baracca di Mauthausen, all'inaugurazione del monumento a Leopold Figl

How far have we got? Austria’s way of dealing with its Nazi past is still questionable

By Wolfgang Schmutz

In a country, reluctant for decades to acknowledge responsibility for Nazi crimes, the public awareness of contemporary responsibility is symbolically high, but not factually. This is valid for Austria as such and particularly its focal point of remembrance and learning at the former concentration camp Mauthausen.

Firstly, an Austrian should state: Ever since the end of World War II Austria officially changed its remembrance policy mainly as a result of international pressure, which triggered reaction by a small circle of invested Austrians. During the past fifteen years, forced to make up for the government involvement of Jörg Haider’s right wing party (FPÖ) at the turn of the millennium, Austria invested foremost in the Mauthausen Memorial. With the resources eventually supplied, a pedagogical infrastructure was created which now caters to over 3000 visitor groups to the site annually, most of them Austrian students. Parallel, a redesign process of the whole memorial was started, resulting in two new exhibitions, dedicated in 2013.

The problem is that, instead of continuing this policy, which earned Austria enormous international recognition, the Ministry of the Interior, in charge of the Mauthausen Memorial, is reversing course or turning back to a more familiar reluctance. In 2013 the director of education’s contract was not prolonged, and the educational development programs as well as guide training were halted. Only now, two years later, a new director of education is installed and this autumn another (desperately needed) guide development program will start. But still, the educational team operates with the same minimal budget, the same limited group of people. At the same time, only a quarter of the overall redesign process is implemented today and nobody knows, if and how this path will be continued. Furthermore, the recommendations of the academics involved in the redesign procedures where turned upside down: The memorial’s outer parts, lacking physical remnants and desperately needing orientation and information for the visitors, were regarded fundamental and proposed as the starting point of the conceptual renewal. Apart from paperwork and a recent project of architecture students from Vienna, nothing moved. The guided tour, though, takes visitors through the parts outside the walls and thereby addresses the involvement of the Austrian society in the phenomena of the camp, it is - apart from small sections in the new exhibitions - only the tours which address the phenomena of perpetrator-ship and the multifaceted ties between Nazi society and the crimes at Mauthausen concentration camp.

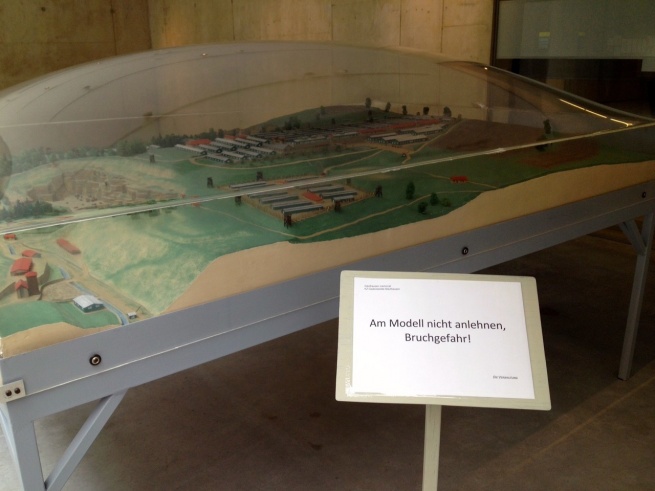

Il plastico del campo nel centro visitatori. Il cartello dice: "Non appoggiarsi sul modello. Rischio di rottura!"

These omissions at Mauthausen Memorial need to be discussed on a higher and broader level - for one Austria’s weak and fragile commitment and then the ridiculous and deeply unprofessional way in which the Republic of Austria “traditionally” deals with the central memorial for Nazi crimes. Contrary to the relatively small efforts, the leading officials in charge manage to frame themselves as profound change makers.

Ever since Mauthausen came into place as a memorial, it was organized as a stage for inner and international politics, framed almost solely from an Austrian point of view. Till today, in contrast to the European and global ancestry of the victims, the subsequently international impact of the crime, the memorial is not regarded an international one, but one presenting Austria internationally. The survivors, their offspring and their organizations are still exploited for this very purpose. Here are a few examples:

- In May 2013, at the official opening of the new exhibitions, survivors were sent over the red carpet as if they would receive Oscars the next minute. During the rehearsal for that staging, the head of the ministry’s department got deeply annoyed by the old people not moving fast enough, not being able to stick to the time-scheme and who sometimes forgot their words, or their personal pieces of memory they were asked to bring in order to store them in a time capsule - for future generations, as it was said.

- Before 2007, there had been an audioguide in several languages. It had to be redone from an academic perspective. The outcome was, that the audioguide was only available in German and English afterwards. For almost a decade now, for this very reason, there is no more audioguide available in Russian, Polish, Hebrew or Spanish, neither in Italian. Serving the former would meet the historical range of Mauthausen, serving the latter would meet visitors' needs, as Italians are the biggest non-German speaking visitor group at the memorial. The memorial is administered and run in a profoundly unprofessional way, with a completely insufficient budget. Under these conditions, any developmental steps, in addition to being fundamentally restricted by the insufficient framework, are often accompanied by qualitative losses in other fields. The outer areas of the camp, where the relationships between society and camp could be emphasized, are till today not part of the audioguide.

- When former Federal Minister Ernst Strasser (Austrian People’s Party, ÖVP) cut the ribbon on the occasion of the inauguration of the visitor center in 2003, together with survivors and the Federal President Heinz Fischer, Strasser took the scissors from a survivor he didn’t know in person and gave it to someone he knew.

- The International Forum Mauthausen (IFM), initiated by the same Ernst Strasser, is the current container for reflections and reactions of the survivor associations, as far as the redesign and current policy of the memorial is concerned. As it is chaired by Austrians and rather a buffer zone for the Ministry than a relevant body, the IFM has to be regarded a fig leaf more than anything else.

- In October 2012, the Austrian People’s Party celebrated the 110th birthday of Leopold Figl at the memorial, inaugurating a new monument. Figl was part-time prisoner at Mauthausen and later awaiting a death sentence in the Vienna Gestapo jail, before the city was eventually liberated by the Soviet army. Figl became the Second Republic’s first foreign minister and later federal chancellor of Austria. In the pre-Nazi period, however, he was a political functionary in the Austrian Corporate State and the head of a paramilitary organization with antisemitic statutes. Figl is mostly known for being involved in the postwar state treaty negotiations. He was, amongst others, responsible for the cancellation of the passage on Austria’s share of the responsibility for Nazi crimes. In the ceremony of 2012 this was addressed in a speech on Mauthausen Appellplatz, given by the then Austrian foreign minister Michael Spindelegger (ÖVP). He qualified Figls attempt to cancel the passage on the share of responsibility as „brave“. While these words where spoken, veteran organizations of WWII were flanking the former Appellplatz with their old flags and insignia.

- In November 2013 Californian students participated in a burial ceremony for ashes, which were found during renovation work. Till today there is no plague at the very place the urns were buried.

Il cartello dice: "Parcheggio, scale e percorsi a piedi non vengono puliti durante i mesi invernali. Si entra a proprio rischio"

It’s the logic of a ministry’s priorities, informed by indifferent Austrian memory politics, framed by an insufficient budget, which strongly influence the decision making processes at Mauthausen. At the same time, most of the professionals at the memorial (archive and pedagogy) have no fixed contracts, and their say is limited by formal and informal hierarchies, which are challenged only minimally from within. Most Austrian historians in the field, a significant number of them engaged by the ministry over the last decades, avoid speaking out loud and clearly what they still know and have questioned rather explicitly, before the recent redesign process started.

The Austrian Mauthausen Committee, an association representing the heritage of the political victims in Austria, strongly tied to the union and religious communities, is deeply involved in these logics. It does not openly and effectively address the failures and deficiencies, which are rather known in the inner circles. Shaping a professionally and ethically adequate memorial is hindered by ties in Austria’s memorial landscape, mirroring the logic of internal politics. This leads to the question, if each and every player really acts according to their societal mandate. Is their agency authentic?

For some two years now, the memorial’s organizational scheme is about to be transferred into a federal agency, some say: into an outsourced low-cost memorial. The place is actually in a fragile situation, just as every transformation process has its instabilities, one might say. But still, within Austria the hesitation to intervene and address the past and current failures is enormous. There is a lack of learning, which could inform the current process or the future setting. Almost everything is negotiated behind closed doors or within a circle of people regarded implicated by the Ministry. This range is tiny. As an outcome, the scenery stays intransparent, aside the bright neon signs continuously blinking, stressing the country’s general commitment.

The international uproar caused by Austrian president Kurt Waldheim’s saying, that in World War II, as hundreds of thousands of other Austrians, he has „only done his duty“, is said to have changed Austria’s attitude towards its past. The Waldheim affair is said to have helped shifting narratives, which ever since have changed from victimhood to responsibility. Given the realities described above, this can be named a delusion.

About the author: Wolfgang Schmutz, born in 1977, Linz, Upper Austria, is currently developing new pedagogical approaches at non-memorial formatted sites and working as a lecturer for “Austrian History, Identity and Remembrance” at the Salzburg Semester of the University of Redlands. A resident of the respective area, he is a guide at Hartheim Castle - Place of Learning and Remembrance, formerly a killing site of Nazi “Euthanasia”. From 2011 to September 2014 he was part of the educational team of Mauthausen Memorial, provisionally co-leading it in the last year. For several years now he is active as a local researcher and production assistant for feature films and documentaries related to the Holocaust (as “Six Million and One”).

Personal comment: As a professional in the field of remembrance, foremost as an Austrian, I’m looking for the voices from outside, calling the actors to the stage. These voices are, in the case of survivor associations, actually voices from within. In fact, I would like to invite all those into shouting, to whom the memorial actually belongs: the citizens of the post-Holocaust world. For the moment it is about enforcing counter-narratives: The more voices can be heard, the more diverse the sorrows are articulated, the more inconvenient it gets for the actors in hiding.

The only sustained way to throw a spanner in the national works at Mauthausen though, as far as I understand it, is to draw a bigger picture, eventually negotiating the lasting omissions and problematic phenomenas in my home country. For this purpose, international cooperation, mentoring and monitoring is a need. The topical danger is, however, that the organizational transfer prepared behind the curtain, is about to be accomplished soon and is going be labeled as progress by Austrian officials. Whilst this narrative might not be challenged, the main players will keep their positions, and as a matter of fact, the cynical character of dealing with the memorial, i.e. Austria’s understanding of its own responsibility, will continue to unfold.