Speciale

Filmmaker Fred Kuwornu on Blaxploitalian and representation in cinema.

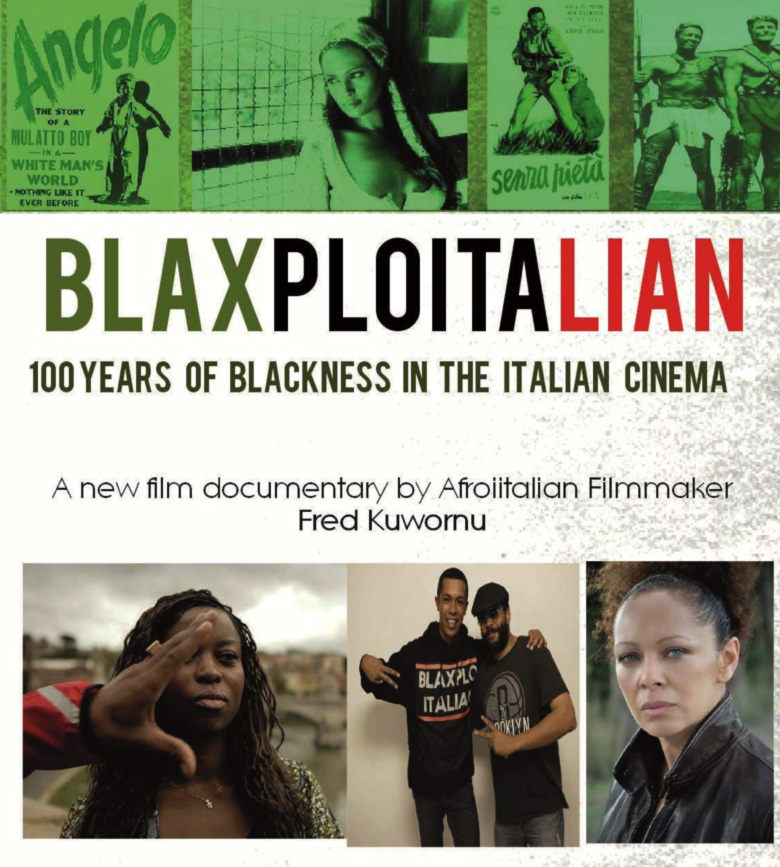

Fred Kuwornu is an Italian-Ghanaian filmmaker and activist best known for his documentaries Inside Buffalo (2010), about the Black American soldiers who participated in the liberation of Italy during World War II, and 18 Ius Soli (2012), about the children of immigrants in Italy and their struggles for legal and social recognition. This summer, he has begun screening his latest film project, Blaxploitalian: One Hundred Years of Blackness in Italian Cinema (supported by a grant from the Lettera27 foundation). A sweeping documentary inspired by Leonardo De Franceschi’s seminal collection L’Africa in Italia as well as Fred’s own experiences in the Italian film industry, Blaxploitalian recounts the century-long yet underappreciated history of people of African descent in Italian cinema. Like Fred’s previous projects, this documentary has an explicit social mission. He is using Blaxploitalian to connect with an international network of activists who are building on the momentum of #OscarsSoWhite and similar conversations in England and France, with the ultimate goal of developing a platform to support advocacy for greater diversity in media.

I have known Fred since 2013; we first met in person in 2014 when I invited him to UC Berkeley for a screening and panel discussion of 18 Ius Soli. We crossed paths again most recently in Bologna on May 13th during the 2016 Human Rights Nights Digital Diversity Filmmaking workshops. Over a light lunch of salad and smoothies, we chatted about Blaxploitalian, the Italian film industry, and the ongoing international debates about representation in cinema.

Fred Kuwornu.

Note: Our conversation, originally in Italian, has been edited for length, clarity, and flow.

Camilla Hawthorne: Can you tell me a bit about where the idea for Blaxploitalian came from?

Fred Kuwornu: The idea came to me because I too have experienced the problem of not being able to work in film if I didn’t want to take on stereotypical parts. I realized that the only roles being offered to me were for the part of “the immigrant.” There was a film by a famous director named Michele Placido, and there I played the part of a character with an African accent—but I took the part because it was an opportunity to work with Michele Placido. Fortunately, after that, my life changed, and I was no longer interested in acting. And so these ideas stayed with me until a few years ago, when I read Leonardo’s book. Reading Leonardo de Franceschi’s book, this idea that I had, I said to myself, “Well, I can actually do this.” Because in reality, there was much more than I had imagined—material for creating something more systematic, like a textbook, something educational. Because obviously, I could also tell this story from the perspective of a person who goes to casting calls, who does everything, and then tells you about the difficulties he or she faces—but that would be something different. I wanted to do this project with more voices. And so that is where the idea came from, about two years ago.

L’Africa in Italia, edited by Leonardo de Franceschi (2013).

CH: It’s interesting because your documentary shows that there is a long, deep history of Afrodescendants in Italian cinema—but this history is relatively unacknowledged, and the actors are not recognized. Why do you think that, outside of Leonardo’s book, this history isn’t more widely known in Italy?

FK: No, there aren’t many people who know this story. In Italy, there are still many aspects of our history that don’t make it into the history books. Even other topics, so…

CH: Like colonialism…?

FK: Colonialism, the liberation of Italy…Obviously for me, I was interested in using Leonardo’s book and the historical context for the battles that people are fighting in the present. Also as a way to stop people from saying that this is a new problem that has only arisen recently, so it will take a long time for it to be resolved. So the idea was to package this story, creating a historical thread that spans at least one hundred years, tying it to the world of film. Because this is a documentary that is interesting even for people who are not interested in social issues, but who work in the world of film, because they like the history of film. It would be as though I had made a documentary about women who worked in Russian cinema. There are people who are fascinated by these topics in film studies. And so, I don’t know the exact reason why the history of the presence of Afrodescendants in Italian cinema isn’t more widely known.

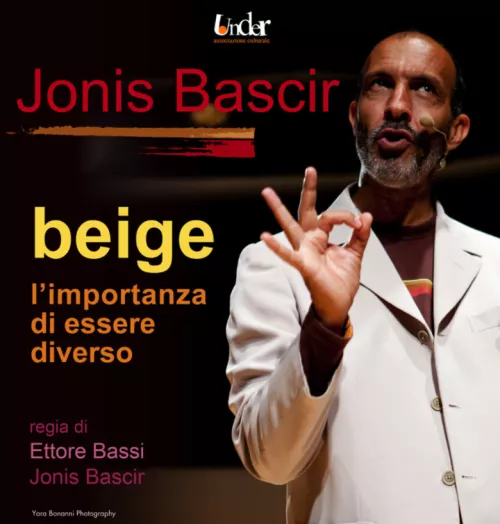

Blaxploitalian film poster.

CH: It seems that you are trying to create a social movement with Blaxploitalian, one that is connected to #OscarsSoWhite, with the work that Idrid Elba is doing in the UK…

FK: Yes, in fact we are working with Kai [Lutterodt] from London—and now I have also contacts with some folks who are working in Berlin, so associations of young people, activists—to create a platform together on this issue. Obviously the larger the platform becomes, the more that prominent figures like Idris Elba and Steve McQueen will get involved. The maturity that some actors are displaying in this moment is very important, and I definitely think that if they know that there is a base of support among everyday people, they will get even more involved, even participating or creating initiatives. In fact, the idea was to create a new initiative in Rome, with the goal of bringing together in October someone from the European Commission, and then Idris Elba or Steve McQueen, and someone from the BBC. In this moment, the BBC is starting a new process in which they are trying to understand what are the ten points with which they can begin to solve this problem of diversity.

CH: At the European level?

FK: No, at the level of the BBC. But the issues are the same, in reality; they are very similar. So we can say that they discovered them first, and they are asking themselves questions now, but the problems are the same. And the solutions they are coming up with are interesting. There are solutions that touch on the method of casting; there are solutions that start from the end-point, that in this moment are attempts to “patch up” the problem a bit. So if you are talking about the end-point that means the screen—in other words, who the actors are. But it’s clear that this process is much longer; it is an effort that is also tied to the beginning stages, the creative process. It’s about putting the preconditions in place such that anyone can become a producer, a studio executive, a director. This is a twenty-year plan that is beginning now; it is structural. But it needs to be done. The other efforts are a sort of therapy—working on the problems that need to be patched up right away—and those can already be addressed in the phase of casting. We need to ask ourselves if 70% of the roles in film that aren’t leading roles, but small, two-minute parts, always need to be filled by the same kind of face. Or can anyone play that part, as long as he or she is good at delivering those lines, at doing whatever is needed for that scene? Because at the moment in Italy, if you want an ethnic minority or a woman, it has to be specified in the casting. So, “Seeking black person for…” or “Seeking woman for…”

CH: But that’s also true in the United States.

FK: I don’t know about the United States, but frequently when a role is not specified, oddly enough the actor always ends up being white and male. This issue needs to be addressed—parts should be specified for certain types of actors only when it’s absolutely necessary. An historical film, yes, because it’s based on history. Or a story in which the leading role was specifically designed and planned…But we need to focus not just on leading roles, but also on the smallest parts. In other words, on the composition of the image you see in the film, in which many different people and things appear, subtly forming an image in our minds.

CH: So that the world depicted in film will more closely resemble the world in which we live.

FK: Right now, it doesn't.

CH: But that’s the goal, right?

FK: Yes and no. In the sense that film was clearly born to make us dream, not to always remind us of what we are now. But then, film evolved, and there are now many movies that purport to tell us about reality. So it is those films that purport to tell us about the real world that, in this moment, are not actually telling us about the real world. No one is talking about films that make us dream, like Star Wars. In fact, the protagonist of the most recent Star Wars film is black, but that is a film of the imagination, so it’s something different. On the other hand, if we see a film based on a story that is more or less realistic—even a comedy—ethnic minorities, etcetera, are always excluded. You never see plurality, or mixed couples. That method of doing casting, I think, needs to be really limited.

CH: Do you think that the situation is more difficult in Italy than in other countries?

FK: Not really. The problem of Italy, like everything else, is that even the film industry is a family industry. They received money in the ’50s from the Americans to make films. Then, in the ’70s the film industry entered into crisis, and the state began to fund Italian cinema with taxpayer money. In the last ten years, Italian films have sold very little, but more or less the same families, or their grandchildren, remain part of this film industry. So there are very old people who are 60, 70 years old, who unfortunately are in the mainstream. But you can’t change them; you just have to wait for them to go away. But in this moment, a new generation has emerged that is communicating through other channels, like the Internet and web series. Or there are even cable networks like Sky. But we are beginning to see that there is some kind of evolution in the works. So the problem of the Italian film industry with regard to the film industries of other countries is just that it is nepotistic; in other words, you only enter the industry if someone invites you in, just like in politics or business.

CH: Do you think that digital media, digital filmmaking, the Internet, and social media have opened up new opportunities for filmmakers?

FK: It is definitely important right now to foster self-determination in people so that they can tell their own stories, and to teach them how to do this in a “professional” manner that can also be commercially successful. But to do this, you have to offer a lot of training. The more trainings you do, the more people will experiment; the more they experiment, the more they begin to network; the more they network, the more changes we will see. So this workshop [the Diversity Digital Filmmaking workshops in Bologna] was just an attempt at organizing a three-day workshop. The idea is to do something a bit longer, lasting one month, where you can really teach, above all, the sensitivity needed to tell a story, even one that isn’t about you. If I were to make a documentary about a Chinese community, I could do it because no one is going to tell me that I can’t do it. But perhaps I could try to tell this story in a different way, and with fewer stereotypes. And so the idea is to develop something longer, extended, that lasts a month, where we can teach these things. So this was a good start, but it’s like going occasionally to Africa and building a well. The structural problem is something else entirely, and needs to be resolved by other methods.

CH: How has living in the United States affected your perspective, the work you are doing?

FK: Living in the United States has changed many things for me, because it has accelerated a lot of ideas I already had. I was able to challenge myself, to learn. In the United States, they are trying to create a multiethnic society—starting however from two thousand mistakes, segregation, things that aren’t going well; but still, there is a compass. And so this has taught me to globalize situations. If I hadn’t lived in the United States, I would have continued doing my work thinking that the problems only existed here. Living in the United States, I have come to understand that most of the problems exist everywhere. Just on the theme of diversity, I was in Ghana and they told me, “It’s like that even here.” Because Ghanaians from the north are always made to work as servants, domestic workers. So living in the United States, being able to travel…and then, it’s probably not just living in the United States, but also living in contexts where I have been able to meet people who are very inspiring—this is a great fortune. And so this has really accelerated my vision that just as the economy has globalized, communications have globalized, everything is globalized unfortunately, even our stories need to be globalized and so problems need to be solved at the global level.

CH: And finally, can you tell us about your next project, Black Italians?

FK: Yes, I’m trying to create a provocative project…to talk about people who are Italians of African descent, who might have been born in Italy or even born in America or Brazil, or even white kids who speak…like this guy, who sent me a friend request; everyone in Ghana knows him. There is an Italian who speaks Twi and Ewe, named Kofi Filippo. I saw that he sent me a friend request, and I thought to myself, “But, this guy is white!” So I accepted his friend request, and I saw that we had friends in common—but they were all Ghanaian. Then one time, I saw a video in which he was speaking to Mario Balotelli in Twi. Later, the Ghanaians were telling me that everyone knows him in Ghana; he is a star in Ghana, this guy! Because he learned from his school friends, because he was curious. This is all to say that with Black Italians, I want to do this—to tell stories about the contemporary Black Italy that emerged in the ’50s…at least, of those people who I can interview, because I can no longer interview people who were in the colonies, etcetera…and arrive at our present day. And as always, the style will be one of trying to help Italy change its attitudes, but at the same time to joke about identity. Because the future of all people is precisely linked to this blending, this mixing.

Traduzione di Laura Giacalone.

With the support of